Celebrating

30 years of excellence and innovation, the Kellogg School

EMBA program has grown from a scrappy local upstart into an

elite international management phenomenon

By Rebecca

Lindell

It

was a sunny spring day in 1976, and the sweater-clad young

administrator from Northwestern University's business school

had just arrived at the University of Chicago's Graduate School

of Business.

The

GSB's Bud Fackler, every inch the elder statesman in

a three-piece suit and tie, strode forth and greeted Ken

Bardach, his invited guest.

This

was no social visit. Bardach was the recently announced director

of the new executive

MBA program at Northwestern, an initiative set to launch

that fall. The program would compete directly with the GSB,

which since 1943 had operated the oldest and most highly regarded

EMBA program in the country

Fackler,

the GSB program director, was deeply curious about the young

upstart's plans.

"Do

you really think you have a chance in the executive MBA market?"

Bardach recalls Fackler asking. "You're going up against

the University of Chicago. We own this market. Why do you

think you are going to succeed?"

Bardach

listed the new program's advantages: "We have a great faculty, location

and curriculum. Of course we are going to succeed."

"I

like your spirit," Fackler said. "At the University

of Chicago, we really believe in competition. I think this

will make both of us better."

Bardach

squared his shoulders. "Let me make this very clear,

sir," he said. "We're not just going to succeed;

we are going to dominate this market."

"I

love it!" Fackler said. "You're really an entrepreneur.

Tell me," he asked, studying Bardach. "Do you have

any questions for me?"

Bardach

paused. As a matter of fact, he did have questions, enough

to keep the old gentleman talking for hours. He dove in, quizzing

Fackler on issues great and small. "How do you make sure

your applicants' transcripts are in? How do you keep track

of admissions? How do you get your faculty to coordinate and

work together?"

Fackler

chuckled. He led Bardach on a tour around his school's executive

MBA facilities as he shared his knowledge. The two shook hands

as they parted.

That

rapport didn't dull the sharp spirit of competition between

the two programs. Within seven years, enrollment at the University

of Chicago's executive MBA program had shrunk by half, while

Northwestern's had doubled. As Bardach promised, the new EMBA

program at Northwestern had overtaken its South Side rival,

and was on its way to becoming the most respected EMBA offering

in the world.

| |

|

| |

Today,

the Kellogg School's academic reach is global, including

an EMBA program in Hong Kong. Here, Finance Professor

Vidhan Goyal teaches Kellogg-HKUST students. |

| |

|

Finding

a vision

The

story of how the Kellogg School built its executive MBA curriculum

from scratch into the pre-eminent program of its kind is one

of doggedness and chutzpah. It is also a story about listening:

to companies, competitors, and above all, customers.

The

champion of that process was then-Dean Donald

P. Jacobs, who assumed leadership of Kellogg in 1975.

From the beginning of his tenure, Jacobs made executive education

one of his top priorities.

"Don

found a vision," says Bardach, now the associate dean

and the Charles and Joanne Knight Distinguished Director of

Executive Programs at the John M. Olin School of Business

at Washington University.

"Executive

education wasn't just a program; it was a vision of where

he wanted to take the school. It was built on the idea of

continual improvement and continually listening to the customer,

designing a strategy and tweaking that strategy, and convincing

the faculty of the viability of the vision."

Kellogg

already offered a number of short-term, non-degree programs

for executives. But Jacobs knew there was more for them to

learn. With the economy of the 1970s in a tailspin, many mid-career

professionals were hungry for the credibility and knowledge

an advanced business degree could provide.

The

faculty, in turn, would gain immensely from the exposure to

current business issues. Executive feedback would help sharpen

their teaching and ensure that lessons were relevant. The

benefits would accrue to students in every Kellogg program.

How

to compete with the behemoth to the south posed a challenge

Jacobs relished. He had noted that the University of Chicago

taught more or less the same curriculum to executives as it

did to those in the full-time program. Jacobs saw that as

a golden opportunity to re-invent the MBA experience.

"These

were mid-career executives, not students in their twenties,"

Jacobs says. "Because they didn't have an MBA, they needed

to be brought up to snuff in some areas. But in other areas,

we could take them even farther. We could take advantage of

the maturity of these executives who wanted to learn."

The

solution was to create a modular curriculum, with each course

broken down into five-week segments. After a Live-In Week

at the start of each year, 24 such modules would be taught

on weekends over two years. The system allowed professors

to tailor the core MBA courses to the needs of executives.

"It

was a highly integrated curriculum," Bardach recalls.

"The professors would talk to each other about what their

needs were. The Kellogg faculty has always been very collegial

and willing to work as partners. The EMBA curriculum took

full advantage of that."

With

the curriculum in place and a faculty that had caught the

fire of Jacobs' vision, the Executive Master's Program, or

EMP, as it was called, was ready to debut. All it needed was

students.

The

effort to wrest a piece of the market from the University

of Chicago took all the charm, savvy and salesmanship of the

Kellogg team. Word went out to friends and alums that Northwestern

was now offering an EMBA. When Jacobs spoke to corporate boards

in the Chicago area, as he often did as dean, he used the

opportunity to sell the EMBA program. Ads in the Chicago

Tribune and The Wall Street Journal also played

a part in recruiting.

In

the end, the school assembled an inaugural group of 52 professionals,

who reported for class on the sixth floor of Leverone Hall

in September 1976.

"We

didn't have the Allen Center in those days," Jacobs recalls.

"We didn't have a cafeteria or anything. We'd bring in

food from a deli and call that lunch. At night we'd go out

to restaurants all around Evanston. We kept innovating. We

had a great time."

Raising

the bar

By

the early 1980s, it was clear those innovations had wrought

something special. The applicant pool was growing. The school

was offering two EMBA programs simultaneously, geared toward

the needs of local students and those who traveled frequently.

The James L. Allen Center — a state-of-the-art building

dedicated to executive education — had opened in October

1979. Its success was inspiring the construction of similar

facilities at rival schools nationwide. Still, the effort

was always on to improve. "Don Jacobs was remarkable

and very smart in the way he went about this," Bardach

recalls. "He kept asking the students, 'What else can

we do to make this better?' He kept probing and probing and

probing.

|

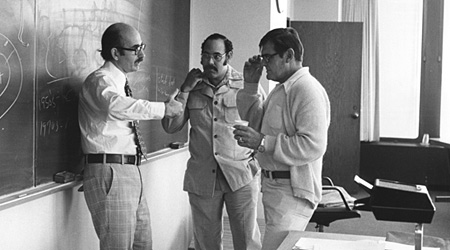

| Continuing

a discussion about marketing after class, Professor Philip

Kotler talks with two executive students in 1976, the

inaugural year of the Kellogg EMBA program. |

"He

was never complacent. He listened to the customer, identified

their spoken and unspoken needs and wants, and responded with

creative solutions."

By

the middle of the decade, the EMBA staff was led by Associate

Dean Ed

Wilson, himself a 1984 graduate of the program. Wilson

and his staff refined the EMBA experience, incorporating as

many elements of the collegial "Kellogg culture"

as possible. That included a student government, a partners'

program, a speaker series, and other activities to build camaraderie.

The self-contained quality of the Allen Center enabled students

to continue their conversations and group work at all hours

of the day.

"We

always told ourselves we were admitting one student at a time,"

says Wilson, who directed the program from 1984 until 1999.

"Each student who enrolls honors us with his or her presence.

It's our responsibility to make sure we make their experience

the best it can be."

As

always, that meant listening.

"The

students would say, 'Ed, you have to build the character and

quality of the EMP experience.' 'Ed, is there a way we can

have a Special K or a GIM program?' They asked if they could

have their graduation in the Millar Chapel with a speaker

of note. I'd say, 'Well, how do we do that? Can you help?'

They would come up with wonderful ideas for how to make this

place better. They were always grateful that we didn't shut

the door."

By

then, the number of executives seeking their MBAs at Kellogg

had risen from about 210 to about 300 per year. The small,

tightly knit Allen Center staff grew ever more adaptable.

"Sometimes

you'd see a staff member running from one part of the building

to another," Wilson says. "I would say, 'Stop. When

you run, it looks like you aren't in charge. Walk, never run!'

we reminded each other.

"I

guess we flew by the seat of our pants a little," recalls

Wilson, now retired. "But in time we began to believe

in ourselves, too."

Shortly

thereafter, a third EMP section per year was introduced. This

one was geared to managers across the country and drew some

overseas students as well. It became known as the North American

Program, and classes met on alternating weekends instead of

alternating Fridays and Saturdays.

The enrollment in EMP now exceeded 400.

The

global leader

By

the 1990s, the Kellogg EMBA program was firmly established

as the global leader in executive education. In 1991, it had

topped BusinessWeek's list of 35

executive MBA programs, a designation it has retained ever

since.

The

Allen Center had undergone four renovations, boosting its

initial capacity of 64 rooms to 150, allowing the school to

offer three concurrent EMBA programs each year. Students traveled

from as far away as Asia to obtain the Kellogg EMBA degree.

The

business world had become increasingly global. Constantly

seeking new horizons, Kellogg announced plans to form joint

programs with several institutions overseas to offer an international

MBA degree.

In

1996, the school established partnerships with the Recanati

Graduate School of Management at Israel's Tel Aviv University;

WHU-Otto Beisheim Graduate School of Management

in Vallendar, Germany; and the School

of Business and Management at the Hong Kong University of

Science and Technology in China. Launching the programs

required the school to put into practice many of its own ideas

about strategic alliances. Concepts about partnership, team

leadership and innovation came into play as the school reached

around the globe to create a new, international learning experience.

The

Israeli program was the first of the joint ventures to debut.

Wilson remembers it as an "extraordinary" effort

on the part of Kellogg and Recanati.

Erica

Kantor, who was EMBA's associate director at the time

and served as director from 1998 until 2003, says, "It

was an attempt to create a place and a classroom where different

groups from all over the Middle East could come together and

have one common goal — to learn about doing business.

"Don

Jacobs and Recanati Dean Israel Zang created an environment

that required students to leave their political beliefs at

the door and work together in the classroom. Teamwork took

on a whole new meaning."

The

strife in the region has not dimmed that concern for the greater

good, adds Kantor, now assistant dean of executive education.

She notes that both Kellogg and Recanati have been "very

protective" of the cooperative spirit in the classroom.

That

attitude pervades the other joint programs as well.

"An

EMBA student is an EMBA student," Kantor says. "No

matter where they live, they all have the same wants and desires

and they all want to be a part of Kellogg."

Still

listening and still looking forward, Kellogg launched yet

another international EMBA program earlier this year, in Miami.

The program draws students from across Latin America.

Now,

as in the beginning, the Kellogg School's leadership continues

to listen closely to its customers, providing the tools for

success.

"Given

the force of globalization, it is important for executives

to have a global mindset — and to refine the frameworks

that enable them to compete in this environment," says

Kellogg Dean Dipak

C. Jain. "With our integrated portfolio of offerings,

the Kellogg School makes it convenient for executives on any

continent to develop the skills of world-class leadership."

|