Rise

of a management titan

1 | 2

Restatement

of purpose

As

the demolition crew moved onto the Evanston campus in June

1970 to dismantle Memorial Hall, onlookers may have wondered

if Joseph Schumpeter's economic theories of "creative destruction"

were being realized. For indeed the old structure was literally

being consumed to give birth to the new.

Memorial

Hall had stood near Sheridan Road and Foster Ave. since 1887,

first housing the Garrett Theological Seminary and then, in

1923, after a $100,000 facelift, opening its doors to accommodate

Northwestern's burgeoning School of Commerce, which had operated

in Evanston out of Harris Hall since 1915. But the program

had actually originated in 1908, located in downtown Chicago

in Tremont House at the corner of Lake and Dearborn. It had

begun as little more than a trade school, a response to what

Northwestern University President Edmund James indicated was

a dire social need.

"The average

business man is ignorant and inefficient and cowardly," claimed

James in 1902. "He is helpless in a crisis."

With an

operating budget of $5,000 and the support of some 60 Chicago

business leaders, notably Joseph Schaffner, university trustee

and a founder of Hart Schaffner and Marx, the commerce school

admitted 165 part-time students in its first year and charged

$75 per annum for tuition, requiring those enrolled to sign

a document attesting to their "good moral character."

Since

that time, the undergraduate business program had grown and

represented not only a proven source of revenue for the university,

but was now "very well respected," according to Professor

Wally

Scott, whose grandfather, Walter Dill Scott served as

Northwestern's president from 1920-1939 and produced path-breaking

research into the psychology of advertising and personnel

management.

Professor

Emeritus Lawrence G. Lavengood also notes the strength of

the program, recalling it as "premier" and one enhanced significantly

after 1950, in part through the support of the Ford Foundation,

which had grown into a national force for education and other

social causes.

Nevertheless,

Dean Barr's Business Advisory Council, itself part of a broader

Management Educational Policy Committee whose membership roster

read like a Who's Who of Chicago's senior business community,

had begun five years earlier exploring the future of business

education, determining that real-world demands called for

a more sophisticated manager than what the undergraduate program

was likely to produce.

"Northwestern

University should strive for an innovative and leadership

position in management education," the Council wrote in its

April 1968 "Proposed Statement of Recommendation." To accomplish

this end, the university should create a school of management

that would "encompass the development of managers, the conduct

of research, and the development of teachers of management

for organizations of all types - business, government, health

and education."

Given

the university's limited resources, the Council, chaired by

Jim Allen, recommended that rather than try to stretch itself

too thin with mediocre results across the board, Northwestern

should take a calculated risk and phase out the undergraduate

curriculum even though it was successful, and despite the

challenges of building a sizable new graduate program.

|

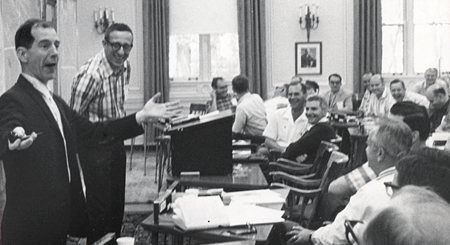

| Another

era: Professor of Business History Gene Lavengood, left,

regales a class in the 1960s with the ready assistance

of Finance Professor Donald

P. Jacobs. Note the ashtrays and cigarettes on desks

and the pipe in Lavengood's hand. |

| |

The Council

based its recommendations upon its research - which included

a broad survey of business and education professionals - that

suggested public organizations faced similar challenges to

those seen in the business world. Furthermore, the complexity

and expansion of the non-business arena presented an "urgent

requirement for trained managers in nonprofit organizations."

What's

more, the Council noted the serious sociopolitical rifts,

including the debate over the Vietnam War, which was then

dividing the country. On many campuses, students wanted little

to do with the "military-industrial complex" and frequently

turned to law schools, rather than business schools, looking

to make a social contribution.

"The intellectual

questioning and striving of our young people today for new

answers and new directions, especially in regard to matters

of public concern, argues well for the appeal of ... a school

of management [which] might help to overcome the disenchantment

of some bright young people with careers in business," wrote

the Council in its recommendations.

Scaring

the hell out of people

The

decision to do away with a successful undergraduate program

seemed dubious to some, particularly those with vested interests

in the curriculum, such as faculty hired specifically to teach

the younger students. And some students themselves felt passionate

enough to protest the decision, which they saw as placing

their careers in jeopardy.

"Eliminating

the undergraduate program changed the faculty to a degree,"

says Ralph Westfall, who was associate dean for academic affairs

from 1965 to 1975. "It was clear that the MBA program was

going to be driving business education in the future, and

this is where you wanted to have your main focus."

To be

successful in this new mission meant recruiting the best research-based

faculty that would, in turn, attract the best students. The

school's Marketing

Department already boasted such paradigm-shifters as Philip

Kotler and Sidney

Levy, and even earlier had influential scholars that included

Richard Clewitt, Harper Boyd, Steuart Henderson Britt and

Westfall himself. Still earlier, Fred Clark's 1922 text, Principles

of Marketing, had helped establish the entire discipline,

while Delbert J. Duncan and Ira B. Anderson produced important

scholarship in the retailing arena. But this level of thought

leadership would now have to suffuse the school, and continue

extending the boundaries of management research.

|

|

| The

arrival of Professor Stanley

Reiter in 1967 was a watershed event, and the school's

research-based faculty would soon hit its stride. |

|

| |

|

Westfall

was among those responsible for bringing in key faculty members,

including Stanley

Reiter, Morton

Kamien, Nancy Schwartz and David Baron, all of whom helped

create the school's potent Managerial

Economics and Decision Sciences Department (MEDS). The

rigorous analytical frameworks of this discipline would influence

all areas of the school, including complementing the important

contributions of the Organization Behavior Department, which

was instrumental in creating the famous Kellogg collaborative

learning model.

"We made

no bones about it when we talked to prospects: This was going

to be a publish-or-perish situation that they would be walking

into here," says Westfall. "If that wasn't what they were

looking for, then they didn't want to consider Northwestern.

If they were looking [to be part of a research-based team],

we had a good product to sell. We were very successful in

recruiting good people."

Indeed,

top-caliber faculty then soon attracted more talent, including

Mark

Satterthwaite, Ehud

Kalai and others.

"Stan

Reiter's arrival here in 1967 was a watershed event," says

Robert

Magee, the Keith I. DeLashmutt Distinguished Professor

of Accounting Information and Management. "Over the next 15

years, he and his fellow MEDS faculty members built arguably

the best economic theory department in the world."

Reiter

recalls his goals upon arriving at Northwestern. "I wanted

to be part of establishing the research foundations in an

MBA school," says Reiter, who was recruited from Purdue where

he had been part of a team that created that school's Department

of Economics. "The mission [at Northwestern] was to train

future managers. Well, in what? Are you going to show them

how to file? There were significant developments going on

in economic theory, statistics and operations research. But

these things were not so sharply separated or defined."

Says Reiter:

"I saw my mission here as bringing in the people to create

a new department out of the ashes of the old establishment,"

one that drew upon a range of quantifiable sciences that were

"foundational ... to lots of things that go on - or should

go on - in schools of management."

MEDS succeeded

marvelously.

"It also

scared the hell out of a lot of people," says Reiter.

New

Dawn

When Memorial Hall came down, more than a building disappeared.

The wrecking ball took with it the vestiges of the undergraduate

program and propelled the school into a future that was uncertain,

but clearly promising and ambitious.

By then,

faculty members were ready for this exciting change, says

Jacobs.

"Nobody

wanted to keep that building up," he recalls. "The wood was

creaky and the faculty offices weren't very nice. It was interesting

looking from the outside, but it probably lived 50 years beyond

its real life."

Faculty,

he says, embraced the hopes symbolized by Leverone Hall, the

newly constructed Evanston home of the full-time graduate

management program, which opened in 1972. Some $5 million

for the project had come in 1968 from Nathaniel Leverone,

the founder and president of Chicago-based Canteen Corp.,

a pioneering vending machine merchandiser. This initiative

formed part of a larger $180 million effort dubbed the "First

Plan for the Seventies," led by Northwestern President J.

Roscoe Miller.

| |

|

| |

Modern

times: With construction on Leverone Hall nearly complete,

Associate Dean Ralph Westfall surveys the progress in

style, circa 1972. |

| |

|

Wally Scott

agrees that these changes brought a new vitality to the school.

"Getting out of downtown Chicago and bringing the MBA program

to Evanston gave you an opportunity to create a different kind

of culture," he says, adding that this kind of "constant reinvention"

has been one of the "remarkable characteristics" of Kellogg.

(The school did retain a downtown presence, of course, in the

part-time MBA curriculum, which remains vital today as The

Managers' Program, directed by Associate Dean Vennie

Lyons.)

Associate

Dean Emeritus Ed

Wilson, hired by Henderson in 1972 as director of admissions

and financial aid, also accents the move's impact on student

culture, which proved especially important as a unique hallmark

for the school. After Leverone Hall opened, "students now

had access in Evanston to the university library and recreational

centers, the religious centers, playing fields, all of which

really changed the character and quality of student life from

being urban to suburban."

Still,

some retained fond memories of Memorial Hall long after its

destruction.

"The Little

Red Schoolhouse was an affectionate name," Lavengood said

in an interview more than a decade later. "But the building

was not a meager one. It had generous halls and there were

many large classrooms with windows you could actually open

and shut. We had high ceilings for high thoughts. There were

surprising nooks and crannies and sudden turns that I think

preached a useful moral lesson, which was: Be sure you know

where you are going."

The Kellogg

School did. It was headed to international acclaim and would

soon land at the No. 1 spot in the rankings.

In

upcoming issues of Kellogg World: We continue exploring

the events and people responsible for taking the Kellogg School

to worldwide renown.

|