|

In

the shadow of the towers

Kellogg

School alums near the WTC when the planes hit share what they

saw, and how their lives changed in the aftermath of Sept.

11

By

Matt Golosinski

| |

|

| |

© Nathan Mandell

|

| |

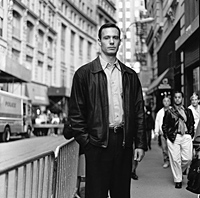

Brian

Lessig '99 fled a 20-story-tall cloud of debris. |

| |

|

It was not

an ordinary dust cloud that chased Brian Lessig ’99 up

West Broadway the morning of Sept. 11, filling him with the

certainty that he was about to die. What pursued the young investment

banker and thousands of others who ran screaming from the epicenter

of the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center was a roiling,

angry avalanche of ash, steel, office furniture and human carnage.

And glass.

Lots of it.

As the

south tower fell, Lessig remembers standing in the street,

mesmerized by the enormity of the spectacle. He watched the

first dozen floors implode one after another and then, only

when it appeared that the blazing skyscraper was toppling

directly onto him, did he run.

“I

had dress shoes on and I ran faster than I’d ever run

in my life,” said Lessig, an associate with Merrill Lynch,

who was late for work that day and so had not entered the

corporate offices located in 4 World Financial Center, about

400 feet from the WTC complex, when the first plane hit the

north tower. He ran for what seemed like blocks, but the nightmare

clung to his heels. “When I looked back, there was a

20-story mushrooming explosion coming toward me. I said ‘I’m

dead. I am going to die.’”

He could

have died earlier that morning. If he hadn’t been exhausted

after a weekend at a Kellogg wedding in Wisconsin, he would

have never hit the snooze button on his alarm. If his buddy

hadn’t bought Lessig a ticket to the Green Bay Packers

game a day earlier, the Kellogg alum wouldn’t have had

to stop, remembering his obligation just as he was leaving

his apartment, and return to his desk inside where he wrote

his friend a check and thank-you note. The effort took only

a few minutes, but minutes wasted that morning may have saved

Lessig’s life.

Other

Kellogg alums found themselves even closer to the disaster

as it unfolded.

|

|

|

© Nathan Mandell

|

|

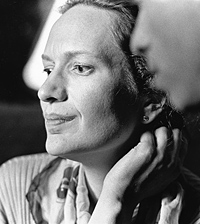

"Everything

looked like a target," said

Liz Kaiser '00. |

|

| |

|

Nowhere

to run

“I was

in a meeting when I heard a big ‘boom.’ I thought

somebody dropped a copier machine in the building,” remembers

Liz Kaiser ’00, an associate at Merrill Lynch. Just three

weeks earlier, Kaiser had transferred from Merrill’s Chicago

offices to Manhattan. She hadn’t even had time to learn

where the stairs were in her new building at 2 World Financial

Center.

Kaiser

and some colleagues gathered along the row of windows in their

40th-floor suite that overlooked the World Trade Center. What

Kaiser saw didn’t make sense: an icon building on fire

and “miniature chairs” tumbling out of it to the

ground 400 feet below. Just as she thought that some “stupid

Cessna pilot” must have accidentally crashed into the

tower, a gigantic fireball erupted from WTC One, rushing across

West Street at Kaiser, threatening to slam into her own office.

“Our

windows shook and we stood there with our eyes wide open,”

says Kaiser. “Then all hell broke loose. Everyone was

screaming. I pulled one of my co-workers off the phone and

said ‘We’re going!’ I didn’t get my purse.”

Kaiser

and her “escape buddy” became part of the herd of

people fleeing the building, filling the hot stairwell and

trying to make their way outside. The crowd remained orderly,

she recalls, although everyone feared it was taking too long

to exit the office. At any moment, they thought, the floors

above them might also come crashing down. With people fainting

and coughing around her, “it took everything to stay

calm,” says Kaiser.

When she

reached the street, Kaiser emerged into chaos. Flames and

noxious smoke engulfed the WTC complex. Sirens screamed. Debris

lay everywhere. Papers fluttered down from the sky. Kaiser

remembers seeing org charts, memos, PowerPoint presentations

-- things that had meant so much minutes earlier, turned into

litter.

“You

could make out the company names on the paper,” she says.

“That’s one of the things that made it so human.”

Kaiser

walked for three hours in high-heeled shoes, joining a parade

of refugees dressed in ash-smeared business suits. The crowd

marched out of Manhattan in near total silence.

As she

fled, Kaiser looked around at a landscape transformed into

something terribly alien. “Suddenly, everything looked

like a target,” she says. “You look at the Statue

of Liberty, and it’s a target. You look at the Stock

Exchange, and it’s a target.”

In fact,

Lessig, who found himself alongside New York mayor Rudolph

Giuliani as the Financial District was evacuated, says that

people didn’t want to walk within 20 blocks of the Empire

State Building. After the second plane hit, New Yorkers thought

the entire city was under attack.

“People

just wanted to get away. They dove into the river and tried

swimming across to New Jersey,” Lessig reports. “They

didn’t even want to be on the ferries.”

Even a

few miles uptown, panic gripped people evacuating their offices

as a precaution. Carol Spomer ’78 was among those worried.

The director of financial services for Entrust, an Internet

security firm, was feeling anything but secure as she filed

out onto Madison Avenue with her colleagues.

“Someone

reported smelling gas,” says Spomer, whose office lies

between Grand Central Station and Times Square. “I had

already seen the two towers go down and now I’m thinking

this gas leak is part of the next terrorist attack.”

She waited

for the subway below her feet to explode. “We felt really

vulnerable,” Spomer says. “I couldn’t sleep

that week. I just kept watching CNN, trying to understand

the reality of this.”

Kaiser,

a native New Yorker, also found herself searching to comprehend

the devastation.

“As

I walked home that day, all I kept thinking about was moving

to Iowa and opening a little one-story shop,” she says.

Pulling

out white-hot steel

Two

months later smoke continues to rise from the volcano of WTC

wreckage that covers more than six acres and whose foundations

reach 70 feet into the earth.

The sickly

sweet odor -- a gruesome reek feeding on plastic, diesel and

a thousand other materials -- has hovered over Manhattan since

Sept. 11 and still remains. It is through the ash and smell

that the tragedy quite literally becomes part of anyone visiting

the scene.

“We’re

still pulling white-hot steel out of the debris, and we’re

going to be doing that for months,” says Lee Benish ’82,

vice president of strategic relationship management for AMEC,

a preeminent international high-rise construction management

company. AMEC was among the handful of companies called upon

by the state and city of New York after the attacks for their

construction expertise.

“The

core temperature of the rubble is still 1,700 degrees,”

adds Benish, an EMP-7 graduate, during an interview in October.

He was at the site hours after the attacks, assisting his

company’s operations. “To see this mass of destruction,

even now, is a humbling, overwhelming experience. Three blocks

away windows are broken. You go to an adjacent building and

there’s a steel beam penetrating the façade.”

Benish,

whose company also is assisting with recovery efforts at the

Pentagon, is surprised the WTC disaster didn’t claim

more lives.

“I’m

amazed we didn’t lose 50,000 people,” he says. “The

tragedy of the numbers killed is horrific, but when you realize

that these 110-story buildings collapsed into 80 feet -- that’s

all the file cabinets, the ceiling tiles, the concrete, the

mechanical systems, rebar floors, 22,000 windows -- you can

imagine how the losses might have spiraled higher.”

The reason

the death toll didn’t rise higher than it did, says Benish,

is that the towers collapsed as they were designed to do:

more or less straight down, preventing excessive lateral damage.

The

aftermath

Many

Americans fear that the events of Sept. 11 may prove less

rare than one would imagine. New Yorkers are universally known

for their toughness, but some, including Rick Linde, Kellogg’s

class representative for 1982, don’t hide their concern.

“Yes,

I’m afraid of living in New York now, but I’ve lived

here with my family for 20 years and to leave would be a cowardly

abdication,” says the executive recruiter for Battalia

Winston, whose offices are located about three miles from

where the WTC stood.

“I

refuse to let these terrorists disrupt my life any more than

they already have,” he adds. Linde believes the best

thing people can do now is follow the advice of Mayor Giuliani,

whose motto has been “Get back to business.” Go

to a show, says Linde, or enjoy dinner out on the town. Spending

money in New York, he suggests, is one way people can help

the city recover.

Such action

may seem difficult, even futile, in the face of an enormous

tragedy, and Linde himself didn’t begin to appreciate

the advice until weeks after the attacks. In fact, he nearly

declined to submit his class news for Kellogg World. But then

he realized that doing his part to maintain the Kellogg network

represented an important contribution to his own recovery,

and the recovery of others.

“Here

I had all these chipper notes from classmates talking about

the new boat they bought,” says Linde, who received the

updates before Sept. 11. “I felt that submitting this

material was totally irrelevant. Then I started thinking about

how things that really help people forge and rebuild human

relationships, like Kellogg World, are even more important

to us now.”

Kaiser

agrees. She says that part of what sustained her through the

attacks was the Kellogg network, especially the hundreds of

alums who flooded the school’s Web site and an associated

site called finebrand.com, either providing information about

a Kellogg

peer, or inquiring about the status of a classmate.

“Knowing

that you have these people looking out for you is just amazing,”

says Kaiser.

| |

|

| |

© Nathan Mandell

|

| |

Doug

Bell '89 volunteered in the rescue efforts by driving

a Red Cross shuttle. |

| |

|

The generosity

of people around the world has also touched Doug Bell ’89,

president of the NYC-based advertising firm that bears his

name.

This benevolence

serves as the counterpoint to the horror surrounding the attacks,

and in some ways, it’s made it more difficult to sort

out his feelings. “There are all these emotional angles

coming at you,” says Bell. “In The New York Times

we’ve read all these stories, thousands of them, about

the victims. At the same time, people are again learning how

to appreciate a nice day and enjoy their friends. It’s

confusing. We don’t yet have a place to put this.”

The “deep,

deep sorrow” created by the attacks has profoundly affected

Bell. “It keeps coming back,” he says. “You

see something on the television or hear a story about someone,

and there’s nothing to say, nothing to do. It’s

really bad.”

But Bell,

like others who volunteered their services after the attacks,

did find a way to help, though he points out that volunteers

with specialized emergency training were the ones in high

demand.

“You

totally feel helpless,” admits Bell, who was “lucky

enough” to help staff a Red Cross center and then work

as a shuttle driver and dispatcher for the agency.

|

|

|

© Nathan Mandell

|

|

| In

the attack's aftermath, Beth Adler '86 says New Yorkers

have become more considerate. |

|

| |

|

For Beth

Adler ’86, until recently a senior vice president at

Sony Classical, the Sept. 11 aftermath has rekindled in her

an appreciation for simple social graces. “People are

starting to be more humane to one another,” she says.

“People in my apartment building are reaching out more

to neighbors, not just coming home with the take-out dinner

and the video.”

Lessig

agrees. “People have really mellowed out since this happened,”

he says.

These

welcome changes come, of course, at a great cost. For Adler,

flying back into New York will never be the same. “Suddenly

your landmarks are gone,” she says. “It’s like

a piece of your heart is cut out.”

When Bell

contemplates the site’s wreckage, he finds himself struck

by the terror and power he sees in the twisted girders.

“Here’s

all this potential energy that was up 110 floors above the

earth,” says Bell. “All the amazing energy and capability

that went into that building came down at one time.”

The tragedy

of Sept. 11 cannot be undone, Bell knows, but part of him

believes that “we still have all that power, that energy,

and the capability to build it all again.”

Ed.

note: In the aftermath of the Sept. 11 attacks, Kellogg World

solicited reactions from alumni who live and work in New York.

We invited those who could attend an October fundraiser in

Manhattan to share their stories with us there for this feature.

We are grateful for their contributions, and for the efforts

of Kellogg’s NYC alumni club which organized the event.

The money raised has been donated to funds established in

the names of the Kellogg alumni who died in the attacks.

"In

Memoriam" for those alumni lost in the attacks of Sept.

11

|